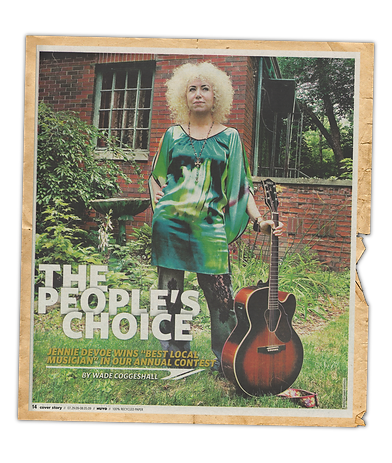

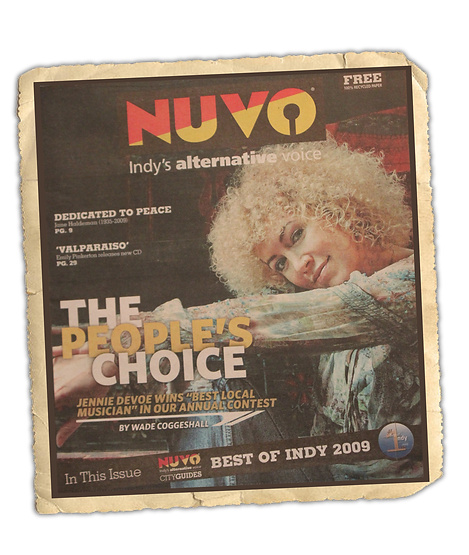

The People's Choice: Jennie DeVoe

Soulful singer-songwriter voted best Indy musician in our poll

By Wade Coggesgall

Hi Jennie,

[We] heard about your success in Indianapolis, and would like to check out your music! Please let [us] know how to proceed.

Thanks,

--Universal Records

Jennie DeVoe gets correspondence like this all the time. She finds it quite flattering. Just not enough to turn ownership of her music career over to someone else.

"I don't think I thought I ever was going to be the next big thing," she says. "My instincts told me I'd get lost in the shuffle."

At least in her adopted hometown, DeVoe, a guitarist and singer-songwriter, has steadily built a cult following behind her smoky sweet voice and folk-blues tenderness. So much so that locals attend her shows in other parts, such as a recent Atlanta gig. Nationally, DeVoe has opened for such luminaries as Sting, Bonnie Raitt and John Hiatt. Her song "How I Feel" was voted Best Pop Song over thousands of entries in a 2004 Billboard Magazine poll. Her music has been featured on network television shows including Dawson's Creek and Joan of Arcadia.

"She just has a very endearing quality," says Brad Holtz, program director for local radio station 92.3 WTTS, which has long championed DeVoe and her music. "There's a lot of local musicians, but we've felt she's just touched so many. Between the sheer amount of albums she's sold and the support she gets at concerts, you can tell there's a genuine connection between her and her fans."

All this has been accomplished, DeVoe says, without "the machine" backing her.

"I think I'm a slow mover," says DeVoe as a way of explaining why, more than 10 years and four studio albums in, she has yet to sign a record deal. "I love music so much I don't want to hate it. And I don't want to hate my life either. I like to have a real life as I'm doing this. Time passes really quickly, and you could wake up and have lost it all. I know people who have. We all do.

"I'm not willing to sacrifice everything to be Super Duper Girl. I think the next big thing is always going to be the hardest thing to be. There are too many people out there to compete with."

Hi Jennie,

This is Oh Boy Records in Nashville, TN. [We were] going through some albums here in the office and came across some of your records, and after taking a listen [we're] pretty impressed (to say the least). [We] did a little research and saw that you're managing your own record label -- still, [we were] wondering if you were planning on coming in or around the Nashville area anytime in the near future? [We] would love to see your live performance.

My first meeting with DeVoe doesn't quite go as planned. The locally owned coffee shop we agreed to meet at in the western suburbs has quietly gone out of business. Instead we settle on one of those corporate, cookie-cutter bistros. ("It's OK," DeVoe assures me. "They give their employees good benefits.").

Indeed, DeVoe is comfortable and sanguine throughout the hour-plus conversation. She's wearing jeans, a blue sweatshirt and flip-flops on a rainy spring morning (still early for her). Other than maybe a tiny gold nose ring, the only thing about DeVoe's mien that may deviate from the typical conception of a Hoosier is her bouffant blond hair.

Her youth in Muncie was archetypal. Her ascent into music as a career, not as much. DeVoe's parents both sang in a church choir. Both play piano. But one of DeVoe's most cogent impressions is of her father's sense of humor. She recalls some of the daffy songs he used to sing to her.

"Early in the morning in the middle of the night, two dead boys began to fight. A deaf policeman heard the noise and he beat the life out of two dead boys," goes one.

Another: "There was a young farmer who took a young miss to the back of the barnyard and gave her a ... lecture on horses, chickens and eggs and told her she had such beautiful ... manners that suited a girl of her charms."

Writing, however, was DeVoe's first passion. She always fancied herself an author first (still does, once she lives a little and actually has something to write about). She thought she could sing from an early age, but was too shy initially to do much with it. DeVoe ended up singing in her church's adult choir only because her mother did. They would've had to get a babysitter otherwise.

"I think it's given me a good education," she says of that experience. "It's schooling by doing it. I didn't really go to school for music. Sometimes I wish I had. Other times I read other people's bios who don't really read music but to me are songwriters I admire. Then I'm OK with it."

Instead, DeVoe abandoned choir altogether by the time she reached high school, you know, because "of course I was way too cool for that." She partied in lieu of honing her future craft.

"I got into some trouble," she admits. "I'm glad I got through it. For me it was like I had all this creative energy that I needed to figure out what to do with."

Enrolling at Ball State University, DeVoe originally wanted to study visual arts. She loves to draw, even made some money at it. After taking some classes, though, she decided to go a different route, graduating in 1992 with degrees in telecommunications and counseling/psychology.

The notion of singing still seemed "the most ridiculous way to make money, until I followed it. You're supposed to follow what you love to do, and the money comes later. If you concentrate on making money, I think you could be unhappy - at least for me."

DeVoe initially tried forging a career she thought would please her parents. But she derived no passion from sitting behind a desk all day. Visions of being trapped in a cubicle, wearing a blue suit, panty hose and "dying a horrible, slow death" began to haunt her. Try as she might, her musical side never fully ebbed.

"I guess the thing you're supposed to do nags at you," DeVoe says. "So I'm glad I had something I was supposed to do."

We are busy passing your CD around our office. We really think it's wonderful! There may be some interest at Lost Highway [current home of Ryan Adams, Elvis Costello, Lucinda Williams, etc.] and possibly Rounder [Alison Krauss, Cowboy Junkies, etc.]. [We] would love to pass it along if you want [us] to. [We are] completely impressed with the packaging and recording. Thanks for sharing your art with us; it is very impressive.

--Universal Music Group

DeVoe's office in the old, stately brick home she shares with her husband Rob, four dogs and two cats isn't much to look at. She keeps her fax machine in a hutch. Yet there are clues that it's an artist's workspace, and not just a room for doing bills.

Jim Morrison's mug shot hangs on one wall (because it looks like Rob when he was younger). There's the framed photograph of Louis Armstrong, autographed by the man himself when he played DeVoe's father's fraternity at Ball State. There also are various NUVO awards on display that DeVoe has collected over the years (honoring her for everything from folk to rock to best overall local talent). A pencil drawing of Tom Waits that Rob bought for her at an art fair graces another side of the room ("He's a freak," DeVoe says of Waits. "Whenever I start feeling kind of boxed in - like there are rules to writing - I put on either Ani DiFranco or Tom Waits. With Waits, it's like you're suddenly picturing movies. He's brilliant.").

Then there are the CDs in DeVoe's office. Immaculately lined shelves and disheveled stacks of them. Everyone from Hank Williams and Led Zeppelin to Mavis Staples and Bobby Gentry.

"Really I like everything," DeVoe says. "I even have Kanye West's Gold Digger. This is kind of my school."

School for DeVoe started with the big band records her father would play in the house. There also were the old soul giants: Aretha, Otis, Ray. She latched onto that gospel feel, but also needed those melodies you could hang a hat on.

"For me, when I write my music, I can appreciate jam bands and all kinds of other music, but I appreciate the old soul stuff," DeVoe says. "I feel comfortable there."

Her impending fourth studio release, Strange Sunshine, puts an appropriate name to her sound, particularly the title track.

"There's an optimistic hope in it," DeVoe says. "It's also not a real perky, happy song. I think I put on a front a lot of times just to be happy. But really I'm a songwriter at heart and I have a lot of things I pull from."

It doesn't always come together smoothly. DeVoe describes herself as a prolific songwriter. It's just that not everything she writes she considers good enough. In fact for every composition she introduces to her audience, there's many more that'll never see the light of day.

DeVoe also can't plan a writing session. She's certainly tried. Despite her distaste for a traditional work environment, DeVoe does maintain an office. Just not traditional work hours or even structure.

"The minute I sit to plan to write, it's like I screw it up," she says.

It alludes to that creative energy DeVoe didn't know what to do with as a youth. She admits to being such a spaz then that her mother got her tested for Attention Deficit Disorder before it became in vogue.

"I'm lucky I can do this," she says. "I don't think I would be able to stay in one place for very long."

DeVoe also says she's suffered from insomnia since she was 15.

"Maybe that's a blessing in disguise," she says. "I find when everything's quiet and everybody's gone, something will hit me. And if I don't make myself write it down, they get lost."

Brett Lodde, her longtime guitarist, can attest to DeVoe's bizarre mode of creativity. "She writes all the time," he says. "It kind of drives me nuts."

That includes halting conversations to write lyrics on any piece of paper she can find. DeVoe carries a tape recorder, but even that's not always enough. Sometimes she resorts to calling home and humming a melody on her answering machine.

"It's all scrambled, but it works," Lodde says.

That manic form of composition translates into equally bipolar subject matter.

"That's me, I guess," DeVoe says. "I'm sad and hopeful. I can see many reasons every day to just give up. I guess songwriting kind of keeps me alive, in a metaphoric way. There's nothing so great as finishing a song and playing it for the first time."

Her wordplay is often and purposely shrouded in duplicity, but it's still metaphorically her. Over time DeVoe discovered her audience liked the vulnerability she projected on stage. She learned to incorporate that into her music.

"But I like music for hopeful reasons, and I don't like to linger in dark, angsty places," DeVoe says. "Maybe on my first record I did, but I was just starting out. I think that's how a lot of songwriters start: They have a lot of angst they've got to get out. Hopefully every record I make will evolve, and I'll just get better. But I also hope I'll be able to put them on and still like them."

[We] have just listened to two of your CDs and [are] very impressed. [We] are blown away by your product. Good luck, and thanks for the great music.

--Umusic

The thought of singing professionally didn't seem so ridiculous by the time DeVoe graduated college. She was so determined to give it a go that she went the commercial route with Bill Mallers and Chris Lieber, co-owners of rippleFX, a project studio in Broad Ripple for commercial advertising.

When DeVoe and Rob moved to Indianapolis from Muncie, she got a job at rippleFX pouring coffee, serving doughnuts and assisting customers and staff. It was the longest she ever worked in one place. It was her school.

Eventually DeVoe worked up the courage to tell Mallers and Lieber she could sing, and offered to do voice-over work for them. It had been a secret she managed to keep well.

"I didn't know she could sing when I married her," Rob admits.

Mallers, who later played keyboards in DeVoe's band for about four years, remembers her as a raw talent then.

"She knew she could sing," he said. "She had tons of soul, and she would just open her mouth and let it rip. It's kind of like watching a wild horse run around in the wilderness, but she wanted to be a racehorse. So she had to be tamed a little bit."

Over some five years, DeVoe learned to harness and control her talent. She did voiceover for a national Meijer ad campaign during those five years, an unheard of length of time in that industry.

"We had loads of fun," Mallers says. "We learned from her as well. We did some pretty creative work together. I'm pretty sure that's something she remembers, in terms of creating music. It should be fun. It's not supposed to be toil and trouble."

She then began to build her career as a solo artist.

"It was like a blessing from God," she says. "It's like, 'Here's your money. Go make records and do this commercial stuff on the side and don't be ashamed of it.' It's a good, honest living and I learned in the studio how to get my chops and sing so many different things."

In 1998 her debut, Does She Walk on Water, was released. Two years later came Ta Da. She still likes those two records, but doesn't really listen to them anymore.

"I kind of feel like I made all my mistakes in front of everybody," DeVoe says. "They were great experiments, but they didn't come out the way I wanted because I didn't know how I wanted them to come out."

That's a major reason why DeVoe sought John Parish to produce her next album, and why Parish agreed.

Parish is best known for collaborating with and producing PJ Harvey. DeVoe has long counted herself a fan of Harvey's.

"I'm not like her in any way, but I'm a fan of a lot of music like that," she says. "I like weird, edgy, wacky kind of stuff. But I know what kind of writer and singer I am."

By extension, she's long admired Parish's production of such artists as The Eels and Sparklehorse. It was his work on Tracy Chapman's Let it Rain that finally prompted her to contact the eclectic Englishman.

"It had such an ominous, stark feel with ambiance, but it wasn't riddled with production," she notes.

DeVoe approached Parish like she has everyone else in her career: She looked up contact information for him online and e-mailed his manager. The initial response was a resounding no. A few more inquires finally convinced them to ask for some demos. After sending some completed material, DeVoe gave Parish recordings of just her and guitar. Then he called.

Assuming an English accent, she recounts what he said: "Yes, yes. I like it. I like your voice and I like your songs, and I think we could do a good record."

Parish admits he has to be picky about whom he'll work with.

"I'm in the fortunate position of being approached by quite a lot of people," he says. "It's just physically not possible to do everything, so I have to make choices."

Those are generally made instinctively. What convinced him to work with DeVoe is "I thought she was doing something I felt I could help her get closer to what she wanted her music to be. That's another reason I'll work with someone: I can see what they're trying to do and they're not quite there, and I think I know how to push it into that direction. Jennie was very much one of those cases. I felt I could help her express more clearly what she wanted to express."

Soon after, DeVoe was en route to Bath, England, to work with Parish on what would become her third studio album, Fireworks & Karate Supplies. Lodde accompanied her to play guitar on the record.

"They made us feel so at home," he says. "I was so nervous. Jennie was paying all this money, and the whole time I was thinking, 'My god, these people work with major stars. Who am I?' But they were so relaxed and polite."

It was the start of a new era in DeVoe's musical passage. More than just exuding soul, she wanted something that sounded timeless. It's a quality also found on the Parish-produced Strange Sunshine.

"Hopefully 10 years from now they're going to sound crunchy and cool and authentic," DeVoe says. "You want something to hold up."

Hi Jennie,

Tell me something -- how come a woman as funny as you writes so many sad songs? If I produced an album for you I wouldn't let you put one sad song on it. Where's that sparkling wit? That personality? That Jennie se qua [sic]?

--Email from music supervisor for Sex and the City, who saw DeVoe perform in Nashville, when the sound went down and DeVoe told funny stories until it was restored

Everyone agrees on one aspect of this year's Vintage Wine Festival. "You couldn't ask for better weather," Rob says behind the stage. "That's the thing about Jennie. She tends to bring the rain."

DeVoe is performing a two-hour set at the annual event in Military Park. This is one of those gigs that includes her full band. Besides Lodde, there's keyboardist Greg McGuirk, bassist Jeff Stone and drummer John Wittmann, who, aside from Lodde, has been playing with DeVoe the longest. Soundman Karl Bruhn is the unofficial seventh member.

There's also backing vocalist Nicole Proctor. She falls into that "superfan" category, having routinely attended DeVoe's shows with her sister until Wittmann introduced them and DeVoe invited her on stage to sing. She liked DeVoe so much she got a tattoo of her before joining the band.

"I like the lyrics; that's what I hear," says Proctor, who has a college degree in opera performance. "It's gotta be someone who can sing with lyrics to back it up."

Wittmann hears that more and more in DeVoe's music as time passes. She and her band have passed the point of needing something to prove. Now it's about having trust and each contributor serves the song rather than him or herself.

"This band is not about anyone, but building a truthful foundation," Wittmann says. "Everyone trusts Jennie to be the songwriting engine."

That devotion is reciprocated.

"I always tell my band thanks for coming," DeVoe says. "Because one day they might not show up, and it'll just be me and I'll have no audience."

But the audience shows up today, and the grass is covered with blankets and lawn chairs.

"I feel silly saying Jennie is from Indianapolis and has a soulful, funky sound, because you already know that," says WTTS on-air personality Paul Mendenhall when introducing the band. There's hearty applause when he mentions copies of Strange Sunshine are on sale at the merch table before its official release, and that DeVoe has inked a distribution deal with Sony for the album.

DeVoe decided it was a good time to make the move.

"They're actually still making money," she says of Sony. "And it doesn't seem like they would, but they want to help independent artists that they're affiliated with, who already have somewhat of a success record. They're not going to pick up just anybody."

It's not the only promotional tool she's added to her arsenal. DeVoe also now has someone booking shows for her and handling promotion. She's also launching a radio campaign for the first time. Already she's been added to 11 play lists on stations from Maine to Texas.

"This is a bike, not a motorcycle," she says of, what is for her, a business juggernaut. "But it's cool."

She's finally feeling comfortable enough to ask for a little help. Early on she met a lot of famous artists who were stuck in audits with their record labels.

"Everyone I talked to said, 'Don't do it,'" DeVoe says. "The advice was live without the fame and just kind of edge your way up. That's what I've done. The fame would be great for money reasons, but with the wrong association it would be the wrong move."

It hasn't come without a price. After Does She Walk on Water was released, DeVoe remembers getting a random e-mail from some radio DJ advising her to sign a record deal as quickly as possible. She's sure she's been written off by some for not pursuing fame as ardently as others.

And she's OK with that.

"I've got this really great audience that's kept with me," DeVoe says. "For me, I've gotten better and better on stage. I have a more at-peace feeling talking and singing. I sing better now. I feel like I tell real stories. [I'm not] just this goofball trying to make it big. I might have wanted that for a while. But guess what: I'm more of a singer/songwriter than I am a pop-hit writer. And I figured it out."

A set of older and newer material -- the plaintive gospel of "Here on Earth" to the Motown mirth of "Exit 229" -- bears that out at the Vintage Wine Festival. Groups of people dance by the third song, the slinky, Southern groove of "Born to be Bad." Afterward, during a performance by the Gin Blossoms, DeVoe signs autographs for two hours.

It's quite a marker for a self-made career. And she's not finished yet. Not when she's striving for the heights of a Bonnie Raitt or a Patti Griffin or a Diana Krall.

"I want to be that good," DeVoe says. "I don't think I'm quite that good yet. I've had my moments, but I don't think I'm quite there yet. I'll just keep going. Until I die."

This article can also be found online here.